After a week of farming followed by a week of sitting on our butts, K and I were itching for a nice long a tramp in the park. Conveniently, the Routeburn Track runs right into the Greenstone Valley and Caples Valley Tracks, so we decided to link up the reputable Routeburn with a lesser known loop around some neighboring valleys for a 6-night/7-day excursion, barely scratching the surface of Mount Aspiring and Fiordland National Parks.

When planning a long, multi-day hike such as this one, there are three things I consider: where to sleep, how to get water, and what to eat. Sleeping on the trail in NZ is rather controlled through the management of campgrounds and backcountry huts. On the Routeburn, space is restricted and fills up fast, so we were beholden to what was available at the time of booking: one night at Routeburn Flats Campsite, and a second night at the Lake MacKenzie Hut. On the Greenstone and Caples Valleys, however, space is plentiful, booking is not required, and the hut facilities are kindly shared with nearby campers so we had the luxury of choosing on the fly whether we wanted to sleep outdoors in our cozy tent or inside by the fire when it was cold and rainy.

Water on the South Island in NZ is generally plentiful and pure. Because there are so few mammals in the country, undisturbed land is usually free of microbial contaminants. One of the pleasures enjoyed by NZ trampers is drinking directly from the mountain streams. In Mount Aspiring and Fiordland National Parks, most backcountry facilities collect water that can be drunk without treatment. However, there are places along the way where agriculture and grazing cattle are encroaching and polluting the rivers.

One very unenjoyable thing about long-distance tramping can be the food cravings you get after living on a diet of dehydrated peas and potatoes for a few days. But there’s a simple trick for eliminating cravings on the trail: eat real food. By my own observation, there appears to be a growing tendency for backpackers to opt for the lightest and littlest “food” options, despite the fact that they are also the least healthy and most expensive. Sure, their packs are a bit smaller than mine, but at the end of the day, after we’ve all walked the same number of miles, the nourishment of real food pays you back in a ways that the Backcountry Meals never can.

Even off the trail, I have yet to tire of an avocado, cucumber, cheese, and mustard wraps for lunch. And after a week of quinoa, veggie, and cashew dinners, my body feels better than ever. No artificial vitamins required. No burger cravings. Just real good food. And all for the reasonable price of $5 per person per meal. (I believe Backcountry meals run roughly $12 per packet, and most people are still hungry after just one).

So with packs stuffed full of food for seven days and six nights, we set foot on the Routeburn Track with an old friend by our side. The Routeburn alone is a 20-mile the hike. Along the way dozens of trail runners whizzed by us wearing little more than a piece of spandex and a body harness of water and energy goo pouches. But while these crazies are racing across the mountain range at no expense, several large groups of middle-aged guided walkers saunter along the path in hoards of twenty or more on their private tour. The buzz of helicopters above the trail is constant as the guided walker’s luggage is shuttled from hut to hut each day. Needless to say, there’s quite a bit of traffic along the remarkable Routeburn Track.

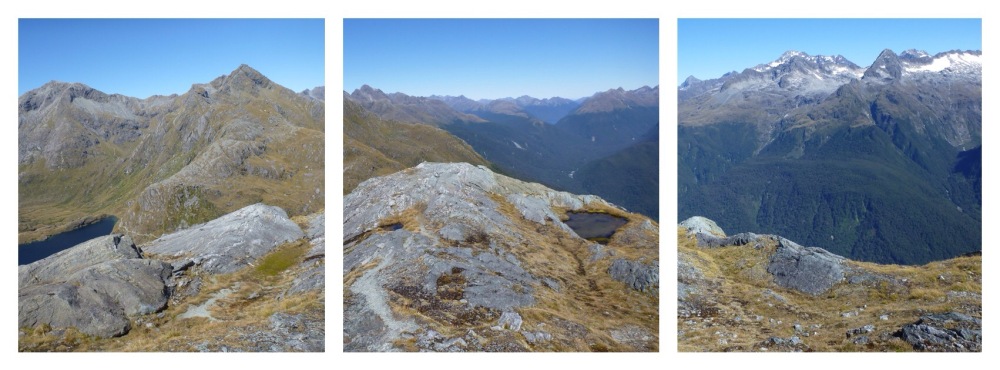

After climbing to Harris Saddle and the nearby Conical Hill, we descended to Lake Mackenzie, where the resident ranger was renowned for the local conversation project he’d started seven years prior: the bird recovery project. He had started this project by asking trekkers for small donations so he could buy and set traps to kill the rodents responsible for the demise of dozens of endemic bird species. Eventually, Air New Zealand caught word and awarded him a large grant to fund the project. Now, thousands of traps line the Routeburn track and beyond, and the songs of a unique cacophony of the native birds is starting to be heard again.

At the end of the Routeburn Track we turned left. Suddenly, the whole landscape changed. The people disappeared. The trail narrowed. We had entered the Greenstone Valley, a valley mostly tramped by locals.

The next four days were a stark change from the regimented crowds on the Routeburn. We walked for hours, passing no one but a huffy bull cow. In the evenings, we enjoyed the comfortable amenities of nearly vacant backcountry huts while being able to retreat to the privacy of our secluded tent at night.

Granted, the views were not nearly as impressive as the days prior, but the solidarity of the trail provided an element of beauty unbeknownst to the Routeburn.

In fact, the free campsite at Greenstone Saddle and the majestic boardwalk atop Mckellar Saddle rivaled our favorite backcountry experiences in the country. We had everything we needed: alpine glow on the mountains, the serenity of solitude, and plenty of good food.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.